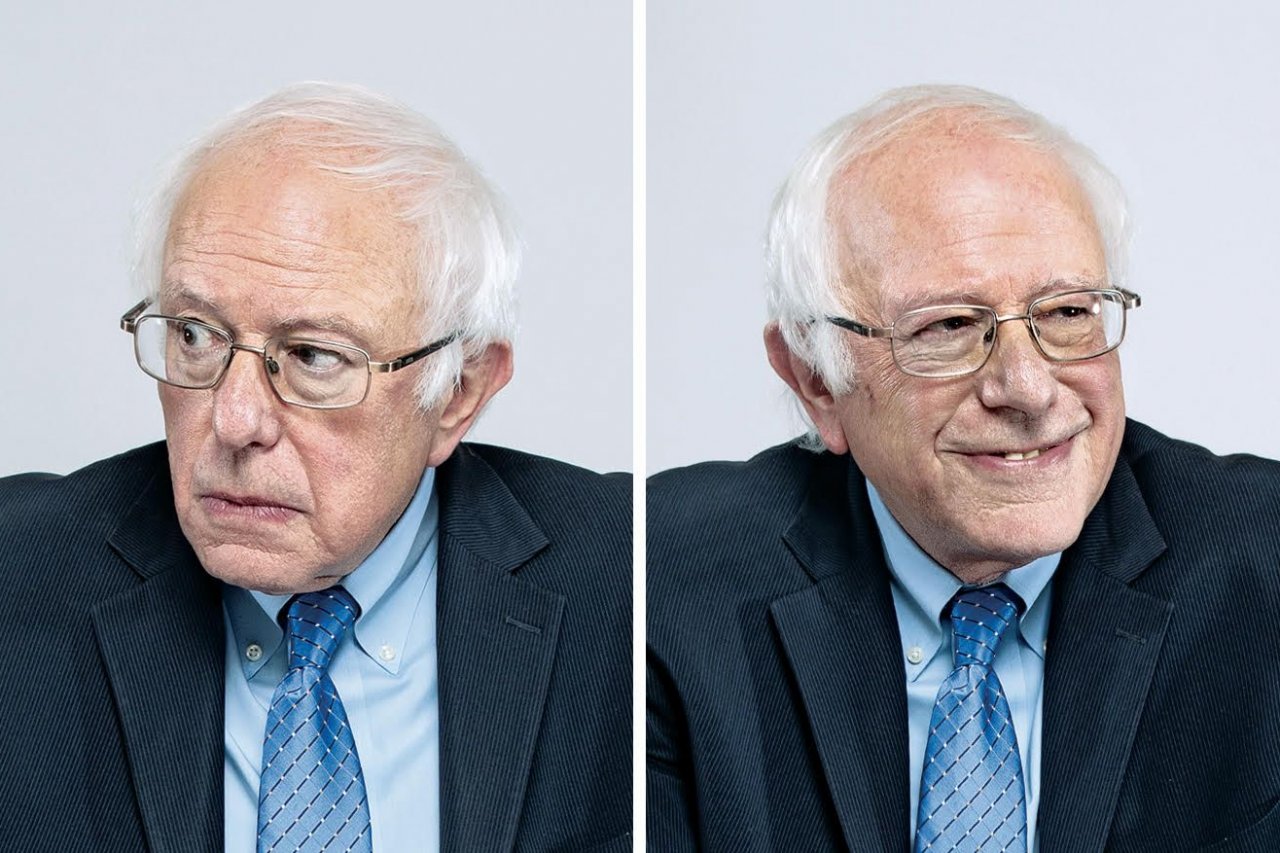

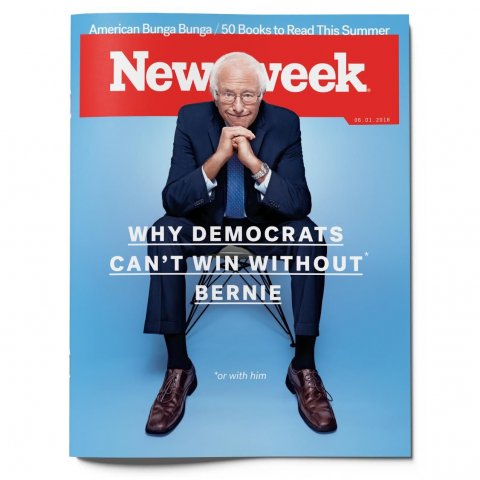

"Please do not think these are somehow radical, or unpopular, or extreme or fringe ideas," Bernie Sanders tells me. It's early May, and the once-and-perhaps-future presidential contender is ticking off progressive policy proposals—his policy proposals—that, in the two years since his loss to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 primary, have rapidly remade the Democratic Party: universal health care, tuition-free public college, a $15-an-hour minimum wage. When he's told that some believe his ideas may be better suited to Finland than Nebraska, Sanders bristles. "Look at the polling," he snaps in his thick Brooklyn accent, which decades in Vermont have not diminished. "You don't have to believe what I tell you."

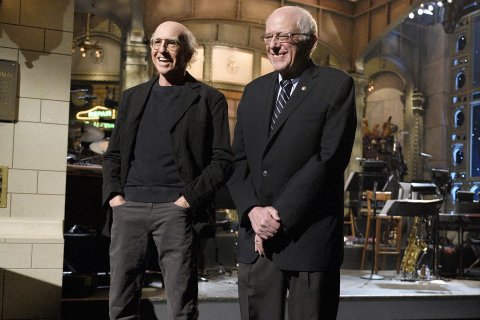

By many measures, he's right. In the two years since his insurgent campaign for the White House succumbed to the Clinton juggernaut, Sanders has gone from cult hero to mainstream dynamo. Larry David can mock him on Saturday Night Live as a cranky, quixotic septuagenarian, but when Sanders endorses an idea, many of his peers in the Senate listen without laughing. The American public has become increasingly receptive to his brand of democratic socialism; once-skeptical centrists have seen the polls and have followed accordingly.

This has resulted in a high-stakes ideological war to out-Bernie Bernie. In March, for example, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of New York endorsed a proposal that would ensure the government guarantees a job to every American. Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey followed with modest legislation, before Sanders bested both lawmakers with a national plan (pay rate: $15 an hour, of course).

This is all new for Gillibrand and Booker, Northeasterners closely affiliated with the centrist donor class that funds the Democratic establishment. For the Sandernistas, however, the focus hasn't changed since Bernie announced his candidacy for president in 2015. Their liberalism is not transactional, pegged to the latest focus-group findings. It is ferocious and uncompromising: Scandinavian to supporters, Soviet to detractors. Sanders and his backers believe the old divides between Republicans and Democrats are being replaced by the far more real rift between those who can't comprehend how anyone could live on as little as $15 an hour and those who spend their working lives making half that much.

Outside Washington, however, this vision is getting a mixed reception. On May 8, in a series of Democratic primaries, establishment figures romped to victory over liberal insurgents. In Indiana, a health care executive who had donated to Republicans won the Democratic nomination for a House seat, besting challengers who backed universal health care. And in Ohio's race for governor, Richard Cordray, the staid former head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, defeated former Representative Dennis Kucinich, the liberal firebrand endorsed by the Sanders-aligned Our Revolution, the political group started by his campaign's alumni.

Within a week, the Berniecrats had rebounded. On May 15, the more liberal candidates beat mainstream hopefuls in Pennsylvania, Nebraska and Idaho. Most striking was the victory of Kara Eastman, a progressive community organizer from Omaha who campaigned for a House seat on a platform of single-payer health care, gun control and marijuana decriminalization. The national Democratic apparatus made no secret of its preference for former Representative Brad Ashford, a centrist who promised compromise. Republicans cheered the result, convinced that Eastman will be the weaker opponent in the conservative-leaning district.

This electoral whiplash has some party leaders afraid the midterms will be more of a referendum on Bernie Sanders than Donald Trump, sapping party resources and potentially costing Democrats their best chance to retake the House in years.

Sanders, however, sees a necessary reckoning. On the day that we spoke, he was headed to Pennsylvania, where he would campaign for John Fetterman, the hulking, tattooed Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor who would go on to oust incumbent Mike Stack. "My role," Sanders says, "is to do everything I can to support progressive candidates."

According to The Washington Post's calculations, Sanders is batting just below .500 in his endorsements, with 10 of the 21 candidates he has supported having emerged victorious. This is a better record than Our Revolution's: Only one-third of its 134 candidates, 46 in all, have won. But losing doesn't bother Sanders as much as it does the ordinary politician. He wants to win, no doubt, but the victories he is looking for are victories of permanence, the kind that are enshrined in history books, not tweets. In fact, Sanders would likely find this entire discussion frivolous. He wants economic justice, and you want to show him some trifling poll?

Winning by losing is a time-honored political strategy—but it does involve a lot of losing. Sanders, the principled warrior tilting at windmills, can make his point by never winning. In fact, losing only bolsters his assertion that politics is a puppet theater, and he is a man who has cut all his strings. And, yes, it is easy to exaggerate the meaning of endorsements for the one making them (Barack Obama endorsed Hillary Clinton, after all, and campaigned for her, but her loss didn't tarnish his reputation). But if Bernie wants to play kingmaker—to have the legacy of Bill Clinton, not George McGovern—shouldn't he be minting a few more regents? And if his ideas represent the future of the Democratic Party, as his supporters claim they do, why have so many candidates espousing those ideas failed to win?

Cracking the Clinton Machine

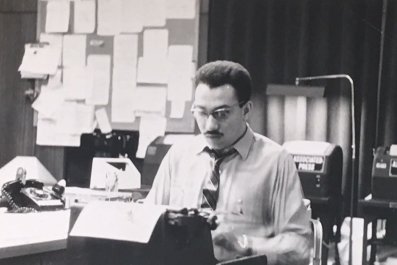

Jeff Weaver has the near-certain distinction of being the only person in American history to have run both a presidential campaign and a comic book store. The shop is called Victory Comics, and Weaver has been its owner and operator since 2009, when he left Capitol Hill, where he'd been Sanders's chief of staff, to spend his days with Wonder Woman and Spider-Man instead of Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer.

In 2015, Sanders asked Weaver to run his presidential campaign. Months later, the Green Mountain State socialist was offering an unexpectedly credible challenge to the relentless Clinton machine and all its supposed affiliates: the coastal donors, the permanent political class, the Beltway pundits. Sanders didn't come all that close, with Clinton earning 3.7 million more votes (as her surrogates will eagerly remind you). Still, there were the adoring crowds, drawn to revolutionary calls to undo inequality everywhere, from pocketbooks to prisons. After Trump's election, "Bernie would have won" became a wistful meme, a sign of things that should have been.

You can't blame Weaver for thinking Sanders was victorious—or for believing that Sanders will win in the 2018 midterms and perhaps in 2020, when he is expected to run for president again. Weaver is not shy on this point. The title of his new book is How Bernie Won. Its last sentence: "Run, Bernie, run."

Weaver's central argument is that Sanders was the first candidate to clearly and honestly describe the destructive economics that have been at work for at least the last half-century, and which have steadily widened the income gap between rich and poor. He was also the first to offer solutions, primarily by returning the federal government to the kind of role it played during the height of the New Deal—that is, more regulation of corporations but also more support for the indigent. Nearly four decades after Ronald Reagan declared that "government is the problem," government would become the solution.

Sanders's disciplined insistence on these points has made people who normally do not care about politics fervent supporters of the 76-year-old Vermonter. They feel he speaks their truths instead of resorting to tested platitudes. Donald Trump's supporters feel much the same way about their guy. (And there is some degree of crossover appeal; one study found that more than one in 10 Sanders voters in 2016 ultimately cast ballots for Trump in the general election.) "That is how we're going to win in the long term," Weaver says of the approach to disenchanted voters. He argues that most independents are not centrists unsure of the choice between Republicans and Democrats but are more broadly dismayed by both parties' inability to offer solutions to real-life problems. "The American people, writ large, want to embrace a progressive economic agenda," Weaver says. That agenda has expanded, most recently, to guarantee a job to every single American, along with health care coverage and a college education.

Progressive can be a dirty word in many parts of the country, nearly as bad as liberal. But when I asked Representative Cheri Bustos, an Illinois Democrat whose district Trump narrowly carried in 2016, whether Sanders's message flops in blue-collar Midwestern territory like her own, she scoffed at the suggestion. "Nobody's sitting around their kitchen table with their teenagers saying, 'Well, these are socialist issues,'" Bustos tells me, citing college affordability and the cost of health care.

There is some truth to that: Recent polling finds that 51 percent of Americans support a single-payer system, while 63 percent support making state college tuition-free. As for Sanders, he has not receded into senatorial senescence since returning to Washington. More than two years since his defeat in the Democratic primary, he's one of the most popular politicians in America; one poll placed his approval rating at 57 percent, 17 points higher than Trump's.

But that approval has not always translated into political currency. Last year, Sanders endorsed House candidates in Montana and Kansas. These were difficult races; both men lost. Later, in a Virginia gubernatorial primary that was seen as a major test of Democratic prospects in the age of Trump, he endorsed liberal Tom Perriello, who lost to centrist Ralph Northam. So did all three Sanders-endorsed candidates for the New Jersey Legislature. In both Missouri and Pennsylvania, he tried to boost state-level legislators. There, too, he failed to make the difference. Wins in some May primaries are encouraging for the Sandernistas, but just as the Democrats need a wave to gain control of the House, liberals need a wave of their own to assert dominance over a party that remains skeptical about their staying power.

So why haven't more Sanders-endorsed candidates won? People in Bernie's camp think the question is fundamentally unfair, evincing the same establishment skepticism that didn't give him a chance in 2015. But they are clearly prepared for the question. When I asked a senior Sanders aide about the senator's mixed record, he promptly produced two spreadsheets. One chronicled the 43 state visits Sanders has taken in 2017 and 2018. The other listed the candidates Sanders has endorsed in 2018. Many of them, like Emily Sirota, running for the Colorado Legislature from the Denver suburbs, are likely to benefit from the attention. The point the Sanders aide sought to make was clear: Bernie is hustling and taking chances to build the progressive ranks, even if some of his picks are long shots.

As for Our Revolution, it has "a pretty damn good win record," says Jane Kleeb, a Nebraskan who sits on the organization's board and is unfazed by the 66 percent of candidates who have lost. "Our country is moving in a more progressive direction," she says.

Not everyone agrees. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has proved a frustratingly pesky frenemy. In the Houston suburbs, for example, Our Revolution supported Laura Moser, a political newcomer who ran a progressive campaign in the crowded Democratic primary. Fearing she could never win a Texas general election with her unapologetically leftist views, the committee launched an attack that branded Moser a "Washington insider" who had only "begrudgingly" left the nation's capital for Texas's 7th Congressional District. It was the kind of internecine fight everyone has dreaded since the Sanders-Clinton contest. Despite the establishment attacks, Moser finished second out of seven in the primary. (In the runoff on May 22, she lost to Lizzie Pannill Fletcher, who enjoyed the support of the Democratic establishment.)

For Sanders, candidates like Moser are far more relevant to the Democratic Party's prospects than donors from Southampton and Beverly Hills. "The business model of the Democratic Party," he tells me, "has clearly failed" in its neglect of the so-called flyover country that Trump won. The Democrats, he believes, cannot be "the party of the East Coast and the West Coast"—even though the biggest reserves of blue districts remain there. They must field progressive candidates in between. The Democratic National Committee (DNC) "is moving in that direction," he says.

The party's leftward shift makes Weaver think that Sanders has not lost. Despite Clinton's victory, Weaver argues the Sanders campaign was proof that centrism was dead, liberalism was alive and the revolution was going to wash over the heartland.

The Tea Party of the Left?

"Jesus." That was the single word a top Democratic operative sent me when I texted her the section of Weaver's book in which he urges Sanders to run for president again.

"You can't say your ideology wins if you lose," notes the Democratic operative, who spoke only on condition of anonymity, for fear that "Bernie Bros"—earnest young men who have taken somewhat too enthusiastically to the prospects of a Sanders revolution—would subject her to a public execution, 280 characters of Twitter buckshot at a time. She argues that Sanders has had little influence on the direction of the Democratic Party: His voice is loud, but in her estimation, many have tuned it out. "They don't win primaries," she says of candidates Bernie supports (we spoke before the May results, in which two Sanders-endorsed hopefuls won in Pennsylvania).

Of course, no politician has a perfect record. What's more intriguing is the manner in which some Sanders-endorsed candidates lose. Take, for example, the Democratic primary for the 3rd Congressional District of Illinois, in the Chicago suburbs. There, Sanders endorsed Marie Newman, the founder of an anti-bullying not-for-profit organization who had never run for elected office before. Newman was challenging incumbent Dan Lipinski, who'd held the seat since 2005. Before that, it belonged to his father. Though a Democrat, Lipinski was a strong opponent of abortion who declined to endorse Obama in 2012.

Despite those renegade tendencies, in 2018 he earned the backing of Pelosi, the former house speaker and the closest thing the Democratic Party has to a kingmaker. Sanders's endorsement of Newman came a week after that, a defiant jab at the Democratic establishment. Lipinski was ready for the assault. Aware of Newman's growing popularity, he cast her as a puppet of the "Tea Party of the left," referencing the potent but disorganized right-wing movement that presaged Trump. The warning worked, and Lipinski won.

The GOP has taken notice and has clearly decided that Sanders is as potent a specter for the right as Trump is for the left. In late April, the Republican National Committee published a blog post simply titled "#Bernified." The premise: Sanders was turning the Democratic Party into the kind of political organ that would have done well in Moscow circa 1936. "By the time we get to 2020, will there be any Bernie policy that the rest of the field hasn't adopted?" the post wondered. "Or will the debate stage be filled with self-avowed socialists?"

The open secret of Democratic politics is that many share this fear, even if they describe themselves as liberals. This is true not only of Bernie's candidates but also of Bernie's ideas. After he introduced his "Medicare-for-all" plan last year, the liberal blogger Ezra Klein wrote that, for all its popularity, the Sanders plan "solves precisely none of the problems that have foiled every other single-payer plan in American history." Numbers aside, the politics of selling Congress on such a plan are inconceivable. Even California—the wealthiest and most liberal state in the nation—couldn't be persuaded to implement universal health coverage, despite a push by the state's powerful nurses union, a group closely aligned with Sanders. Sacramento, where the Democrats have a supermajority, killed the bill because nobody knew where the funding was going to come from. "This was essentially a $400 billion proposal without a funding source. That's absolutely unprecedented," Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon told the Los Angeles Times. "This was not a bill; this was a statement of principles."

Other signature ideas face similar problems. Free college would cost some $75 billion a year, which Sanders proposes to cover with a Wall Street tax. It is difficult to imagine Republicans, or even centrist Democrats, endorsing such a plan. Universal basic income, which Sanders also supports, would cost $900 billion, more than what is allotted annually to the Pentagon. Meanwhile, the Trump administration has mused about cutting Meals-on-Wheels ($517 million from Washington). Sanders is not a details guy, however. He's winning the ideas war, which is the one he thinks he needs to win. "Virtually all of the ideas I have been fighting for now have significant support among the American people," he says. Presumably, he'll crunch the numbers later.

Either way, there is some support for this vision among high-ranking leaders. "The electorate is more progressive than the people who represent them," says Representative Keith Ellison, Democrat of Minnesota and deputy chair of the DNC. A close ally of Sanders, Ellison believes that Washington's political class does not understand the plight of the common man, which is why Sanders's ideas sound more outlandish inside the Beltway than outside it. "The average person in the Congress is a millionaire," Ellison correctly asserts. "If we fundraise at the country club, if you're munching on hors d'oeuvres, the conversation is not going to revolve around layoffs at the local Toys R Us."

But if Sanders has an ability to inspire, he also has the ability to exasperate, in particular when it comes to Democratic insiders who don't think he understands how politics works. "If hubris and the successful pursuit of headlines were genuine indicators of political aptitude, perhaps Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) would actually be the Svengali he's presently being sold as," opened a withering 2017 column by Michael Arceneaux on The Root. Its title: "Shut Up, Bernie Sanders."

Philippe Reines, a former top Hillary Clinton aide, believes that Sanders suffers from "ideological naïveté," as he put it in a recent conversation. Bernie, he argues, misread the electorate. Whereas Sanders saw the support he enjoyed during the Democratic primary as an upswell of liberal sentiment, Reines saw something much less transformative: hunger for something, anything not named Clinton. Ever since, Reines says, Bernie has been overestimating the support for his policies. That would help explain why the candidates he backs haven't been winning in big numbers in '17 and '18. Reines doesn't think '20 will be any different, should it come to that. "The Bernie that we saw in 2015," he says, "I don't think that's gonna translate to 2020 in some magical way."

Run, Bernie, Run

In mid-April, the New Hampshire Democratic Party held its annual McIntyre-Shaheen 100 Club Dinner in Nashua, a town near the border with Massachusetts. On the 31st page of the program, there was an ad that caught attendees' attention, solely because of who'd purchased it: "Friends of Bernie Sanders." The ad vowed to work with the state's Democratic Party "in 2018 and beyond!"

Beyond the midterm elections lies the presidential campaign, in which many expect Sanders to challenge Trump—as well as perhaps a dozen candidates from his own party. When I asked him about it, Sanders dismissed the question, the way every eventual candidate does. Of course he isn't running. The only people who declare this early are kooks.

At the same time, Bernie is acting like a candidate. He will publish his own book, Where We Go From Here, around the time of the fall midterms, when attention turns to the presidential primaries. He has been to Iowa at least twice. And though he stayed away from Alabama during last year's high-profile Senate campaign, he recently ventured South in an effort to appeal to black voters.

"The one thing that Sanders has is that people like him personally," says Mark Penn, a veteran pollster who used to work for Bill Clinton, praising Sanders for his "spunk." He compares Sanders to Obama, because, he says, both men were liked better than the policies they proposed. And he contrasts Sanders with Trump, who is loathed by many, even as some of his policies enjoy support.

Penn's polling has arrived at a conclusion that would surprise no one who has ever shopped at a Walmart or Target: The electorate remains "quite strongly capitalist in nature," while rejecting socialism as a "threat." The one policy proposal of Sanders that people have warmed to, Penn finds, is universal health care coverage.

Like most everyone else I spoke to, he thinks that Sanders will run in 2020. Not everyone thinks this is a good idea. Former Vice President Joe Biden also knows how to appeal to the working class, but unlike Sanders, "he's more attuned to the winning Democratic message" of liberal gradualism, as Penn puts it, less likely to go rogue. Elizabeth Warren is just as progressive but less anathema to the Democratic establishment. "He's going to do what he's going to do," says Reines, the former Clinton aide, with something rather like resignation. "It's not necessarily what's best for the Democratic Party." Sanders would disagree with that assertion. If he didn't think he knew best, he would have gone quiet long ago. And his case for a shake-up is compelling.

During the eight years of the Obama presidency, the party lost hundreds of legislative seats around the nation. It lost both chambers of Congress. Then it lost the presidency. For Sanders, these were signs of a profound disease within the Democratic establishment, one that's grown fat on donor dollars and voter data, but also increasingly divorced from ordinary people. Though he may bristle at the notion, what he is prescribing will amount, for most Americans, to an experimental treatment. The question is how many of them actually want it.

Additional reporting by Marie Solis.